Chapters

| 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 |

| 08 | 09 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 |

| 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 |

| 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 |

| 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 |

| 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 |

| 64 | 65 | 66 |

Isaiah – When Heaven Crashes into History

What’s this Book All About?

Isaiah is like watching a master painter work on a massive canvas – sometimes close-up detail work, sometimes broad sweeping strokes that take your breath away. It’s a prophet wrestling with God’s holiness and humanity’s brokenness, painting a picture of judgment and hope that would echo for seven centuries until culminating with King Jesus.

The Full Context

The book of Isaiah spans roughly two centuries of Israelite history (8th-6th centuries BCE), making it one of the most complex and layered prophetic works in Scripture. Isaiah ben (son of) Amoz prophesied primarily during the reigns of Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah in Judah, a time when the Assyrian Empire was reshaping the ancient Near East and the northern kingdom of Israel was about to fall. The prophet addressed a nation caught between political alliances and spiritual apostasy, warning of coming judgment while offering glimpses of ultimate restoration. What makes Isaiah unique is how it addresses both immediate historical crises and distant eschatological hopes with equal intensity and conviction.

The book’s structure reflects this dual focus – scholars often divide it into “First Isaiah” (chapters 1-39), dealing with 8th-century Assyrian threats, and “Second Isaiah” (chapters 40-66), addressing 6th-century Babylonian exile and return. But rather than viewing this as evidence of multiple authors, it’s better understood as a prophetic telescope – one prophet seeing both near and far fulfillments of God’s purposes. The literary artistry is breathtaking, moving seamlessly between courtroom scenes where God prosecutes His people, tender shepherd imagery, and apocalyptic visions of cosmic transformation. Isaiah introduces themes that will dominate biblical theology: the holy remnant, the suffering Servant, the Branch of David, and the new heavens and new earth.

What the Ancient Words Tell Us

Isaiah’s Hebrew is some of the most sophisticated poetry in the entire Hebrew Bible. When Isaiah receives his call in Isaiah 6:3, the seraphim cry “Kadosh, kadosh, kadosh” – holy, holy, holy! This isn’t just repetition for emphasis; it’s the Hebrew way of expressing an extreme triple superlative over the usual double repetition. God isn’t just holy – He’s the holiest of the holiest of the holy, completely set apart from everything else.

But here’s where it gets fascinating: the word kadosh doesn’t originally mean “morally pure” like we think. It means “separate, set apart, other.” When Isaiah encounters this otherness of God, his response isn’t guilt about sin – it’s terror about being utterly outclassed. He cries, “Woe is me, for I am undone!” The Hebrew word nidmah literally means “I am silenced, brought to nothing.” It’s like a amateur musician suddenly finding themselves on stage with the London Symphonic Orchestra.

Grammar Geeks

Isaiah loves wordplay that English translations can’t capture. In Isaiah 5:7, God looked for justice (mishpat) but found bloodshed (mispach), for righteousness (tsedaqah) but heard cries of distress (tse’aqah). The Hebrew words sound almost identical – it’s like saying God wanted justice but got “just ice.”

What Would the Original Audience Have Heard?

Picture yourself as a resident of Jerusalem in 701 BCE. The Assyrian war machine has already devoured the northern kingdom of Israel, and now Sennacherib’s army is camped outside your city walls. Your king, Hezekiah is sweating bullets, and everyone’s talking about cutting deals with Egypt or Babylon. Into this chaos steps Isaiah with his wild pronouncements about trusting in the Holy One of Israel.

When Isaiah talks about nations being like “a drop in a bucket” (Isaiah 40:15), his audience would have felt the absurdity viscerally. Assyria wasn’t just powerful – it was the ancient world’s equivalent of the Death Star, systematically obliterating entire peoples. Yet Isaiah insists that all these empires are like grasshoppers before Israel’s God, יהוה (Yahweh).

The original audience would have also caught political undertones we miss. When Isaiah speaks of a coming King from David’s line (Isaiah 9:6-7), he’s not just being spiritual – he’s making a political statement about legitimate authority in a world where might makes right.

Did You Know?

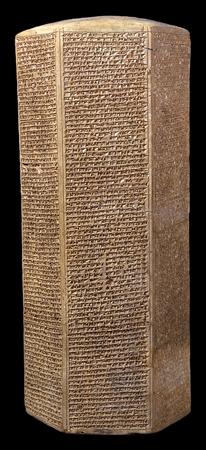

Archaeological discoveries have confirmed many of Isaiah’s historical references. The Sennacherib Prism, discovered in 1830, corroborates Isaiah’s account of the Assyrian siege of Jerusalem, with Sennacherib boasting he had Hezekiah “shut up like a bird in a cage” – but notably never claiming to have captured the city.

Wrestling with the Text

Isaiah contains some of the Bible’s most beautiful promises of peace and restoration, right alongside some of its most terrifying descriptions of judgment. Isaiah 2:4 gives us “swords into plowshares,” but Isaiah 13:16 describes babies being dashed against rocks. How do we hold these together?

Isaiah seems to see history as moving in cycles – rebellion leads to judgment, judgment leads to purification, purification leads to restoration. But it’s not just cyclical; it’s spiral. Each turn of the wheel moves closer and closer to an ultimate resolution where God’s justice and mercy meet completely.

The suffering servant passages (Isaiah 42:1-4, Isaiah 49:1-6, Isaiah 50:4-9, Isaiah 52:13-53:12) present another puzzle. Is this mysterious figure Israel? A future prophet? Someone else entirely? The text seems deliberately ambiguous, as if Isaiah is seeing a figure who is both representative of Israel’s calling and the fulfillment of it. This is the conundrum of my Jewish friends who are uncomfortable with Jesus being their crucified Messiah. To which I say, have you considered Zechariah’s prophecy of when Israel meets their Messiah. In it they ask Him about His wounded arms, and He says, ‘These are the wounds I received in the house of my friends.’ He still calls you friend even after what He went through – now that’s love!

How This Changes Everything

Isaiah doesn’t just predict the future – he reshapes how we understand God’s relationship with history. Before Isaiah, many Israelites thought of Yahweh as their tribal God who would automatically protect them. Isaiah reveals a God whose holiness demands justice, even from His own people, but whose love refuses to let that be the final word.

The book’s vision of restoration isn’t just about Israel getting its land back. Isaiah envisions a complete cosmic renewal where predators and prey lie down together (Isaiah 11:6-9), where physical disabilities are healed (Isaiah 35:5-6), and where all nations stream to Jerusalem to learn God’s ways (Isaiah 2:2-3).

This isn’t escapist fantasy – it’s a vision that gives meaning to present suffering and hope for ultimate justice. When Isaiah talks about God making “beauty from ashes” (Isaiah 61:3), he’s not offering cheap consolation. He’s saying that God is the kind of Artist who can take the worst raw materials and create masterpieces.

“Isaiah doesn’t just comfort the afflicted – he afflicts the comfortable, showing us a God whose love is too fierce to leave us unchanged.”

Key Takeaway

Isaiah teaches us that God’s holiness isn’t the opposite of His love – it’s what makes His love transformative rather than merely accepting. True hope isn’t wishful thinking; it’s seeing present reality through the lens of God’s ultimate purposes.

Further Reading

Internal Links:

External Scholarly Resources: